Why estimations don't really work

I’ve been through a fair bit of teams; and I have built and managed my own share of them as well. I’ve seen teams that estimate in hours, I’ve seen teams that estimate in points, in complexity, in t-shirts, and in pokemons. Okay, I haven’t seen teams estimating in pokemons. But, I dare to say that they’d have exactly the same outcomes in their delivery as everyone else. Why? Well, because…

A lot have been said so far about futility of estimations, and yet it’s 2023 out there, and teams still dutifully practice the estimations drama. And so, I’m here to “help”.

Quick math

Before you can fully understand my point, I feel it’s necessary to arm you with some knowledge. Some of you are well versed in math and statistics, and I apologise for dragging you through this. But, some are not, and I hope you’ll find it useful.

Lets start with basic stats terminology:

average, ormeanfor those in the US - means what you think it means. A sum of the elements divided by the number of elements. The average of1,2,3is2, and the average of3,2,1is2as well.median- refers to the value in the middle of a list. The median value of1,2,3is2. But the median of1,1,4is1, which is different from the average, which is still2in this case.mode- refers to the most commonly appearing value. The mode of1,1,2,4is1, and the mode of1,2,3,3is3. Obviously, there can be more than one mode: the list1,1,2,3,3,4has two modes1and3

Quick stats

When we’re talking about statistical analysis, we’re normally talking about probabilities; more specifically we’re talking about probability distributions. At which point people think about bell curves and what’s known as the “normal” distribution.

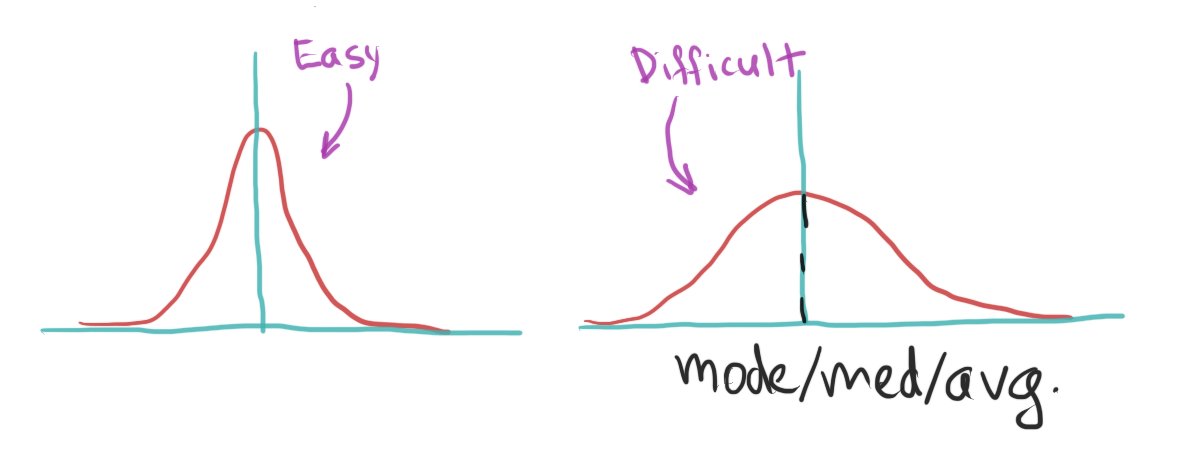

In a normal distribution, the mean, median, and mode mean exactly the same thing: the peak of the bell curve. And the more difficult a problem is the more shallow the graph will be.

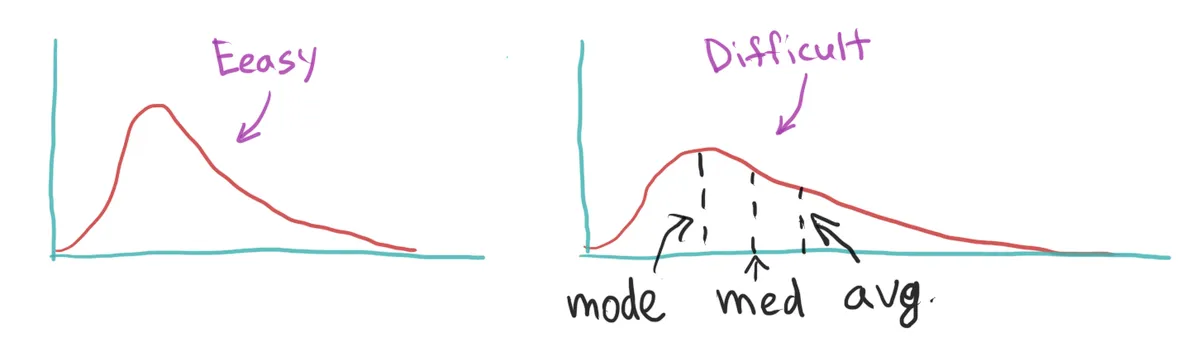

A normal distribution is not the only type of distributions. Some of the most important cases — and estimations fall into this category — are not bell shaped, they are skewed and known as asymmetric distributions.

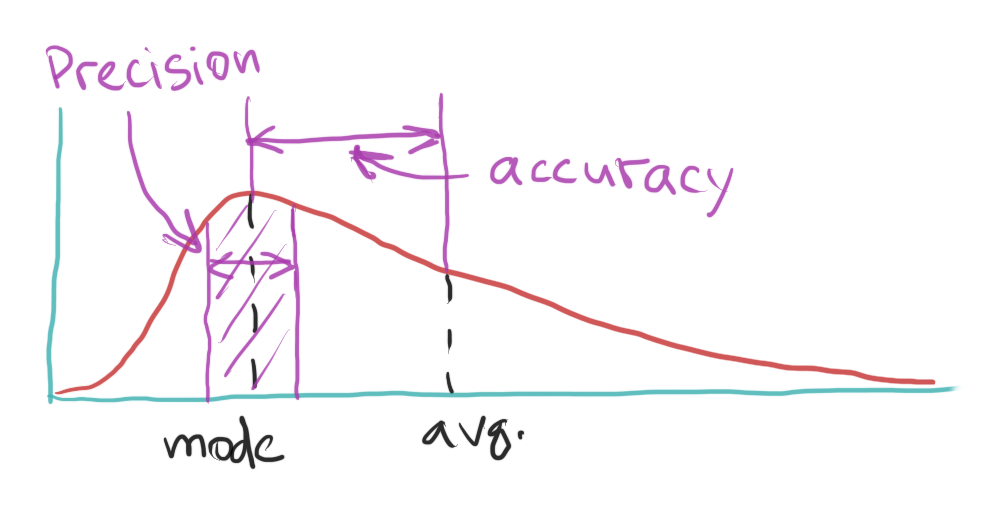

The mean, median, and the mode will be three different things in this case. The reason for it is that the area under the curve represents all the possible cases, and there are more possibilities on one side of the peak than the other.

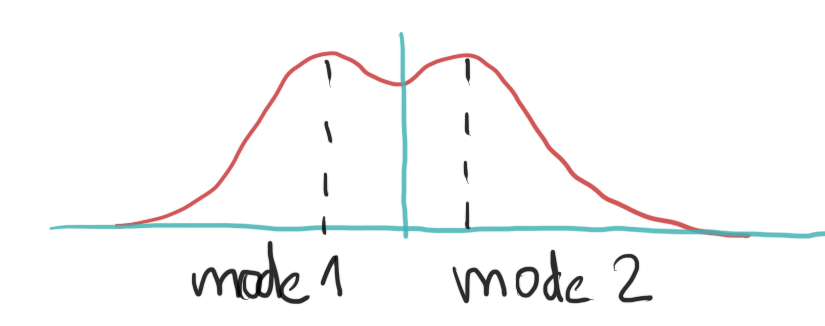

And, while we’re on the subject of weird distributions, there is yet another probability curve to keep in mind. Sometimes, there are more than one common outcome, and that will result in the curve having multiple peaks. Those are called multi-modal distributions.

Those often happen in complex situations with lots of dependencies and non-homogeneous data sources. For example, if you take the distribution of people heights in a group that has a 1:1 ratio of males and females, you’d see to peaks, one for the average female height and one for an average male height.

Estimations math

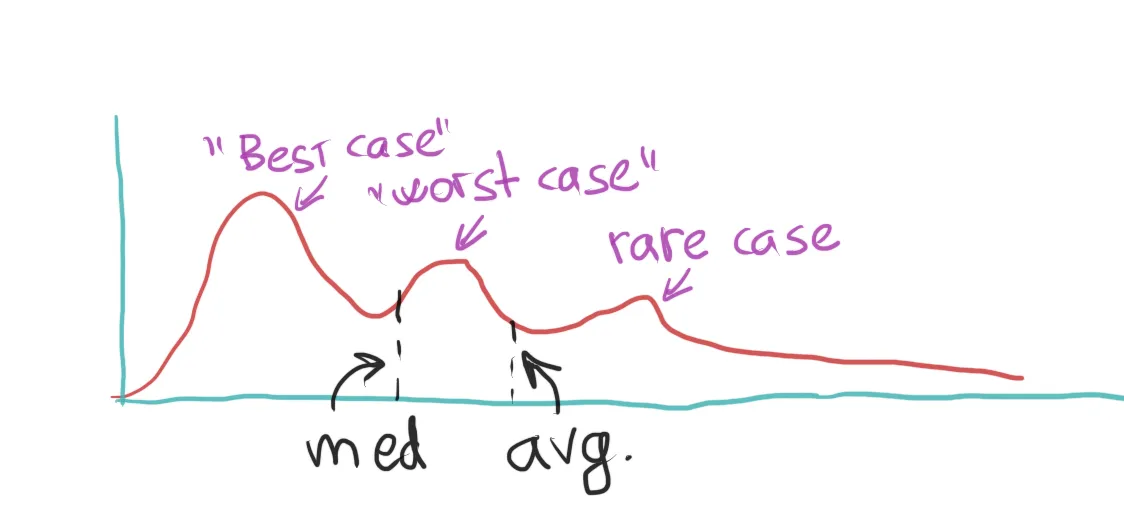

When it comes to estimations, it doesn’t really matter what system a team uses, they all follow the same mathematical principles. They all go from zero to infinity, and the probability of them being accurate can be represented by an asymmetric, often multi-modal, probabilities distribution curve

The more complex a task is, and the more dependencies it has, the shallower the graph will be, with more peaks showing up. At some point it gets so muddy, that a drunk monkey throwing a banana at the chart would have roughly as much luck with the estimation as any member of the team.

However funny that sounds, that is not the actual problem here.

So, what is the problem?

The problem with the picture is this. When you’ve been asked to estimate something, what you think about is the mode value, or the most commonly appearing outcome in your experience. And the more experienced an engineer is the more consistent they will be at pointing out the value.

But, what’s really implied here is the average value. Because the general mindset in estimations based planning is that you don’t have to be accurate with each estimation, the law of averages will kick in at the end of the sprint and sort it all out. And it will. Just not the way you think it should.

What everyone is missing is the fact that in an asymmetric probabilities distribution, the average is always larger than the mode or the mean value. Meaning that your averages will always be larger than your estimations. And the more complex the task is, the bigger the gap. The work therefore, on average, will always take longer than estimated.

Because the math says so.

Accuracy and precision

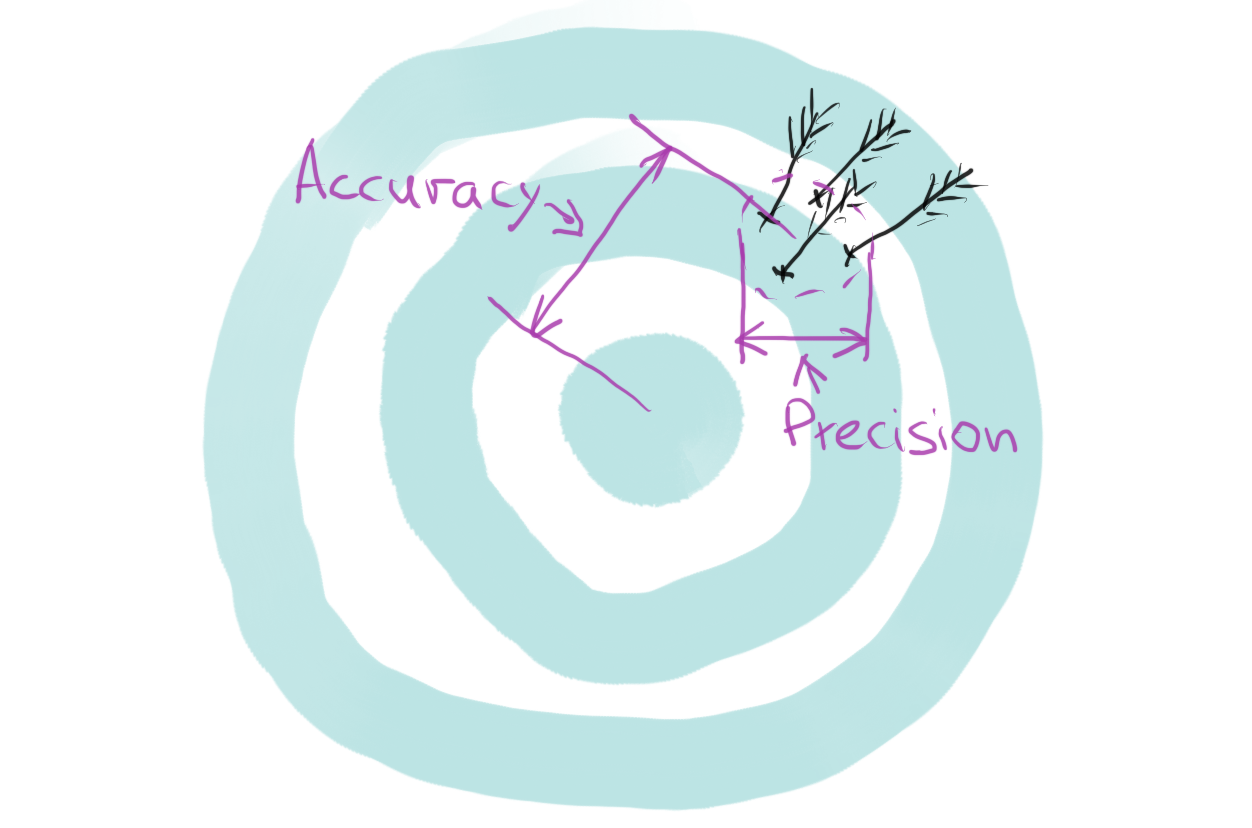

When it comes to any measurement, there are two elements to the problem, accuracy and precision; or sometimes they go by the names of bias and variability.

precisionorvariabilityrefers to how wide spread the measurement results areaccuracyorbiasis how close the results are to the actual/true value

Or, in case of the estimation probabilities distribution graph, it looks like so:

You see now, you can whip your team endlessly into “getting better at estimations”, working on optimal tasks granularity, etc. And it all will go wrong every single time. Because you will push the team to optimise for the accuracy of the mode value estimations, they will always be aiming at the wrong thing. And then, the team will be repeatedly punished by the large gap between the mode and average values.

This is called a “high precision, low accuracy” situation. It’s like trying to measure the dimensions of a piece of gooey rubber with high quality calipers.

And so, what do the teams do? They pad the crap out of their estimations until the mode spread overlaps with the average value. Everyone does this. Either explicitly, or implicitly by using gimmicks like fibonacci numbers, and averaging team members estimations.

The ugly truth

The truth is that nobody knows how long work will really take ahead of time. Because nobody experienced the tail end of the distribution where the average lives. And the more complex a task is, the more dependencies there are, the less probability that any estimation will be correct.

Work, especially the hard, critical work takes as long as it takes. Estimations just lul you into the false sense of control over the situation. Nobody really knows the answer, but when you produce a number, any number, it gives a plan a flair of legitimacy. And off you go, telling your boss when it’s going to be done.

The final chord

And that’s not the worst part yet. Okay, suppose, I’m full of it. Suppose all that math above doesn’t really exist or totally wrong. Let’s pretend for a second that your estimations actually are accurate. Like for reals accurate. What do you think is going to happen?

Suppose, you have estimated a task will take, say, 4 hours. A PJ sandwich falls on the jam side every other time, meaning you still have the variability in your estimations. And, you might finish it in 2 hours, or you might finish it in 6 with roughly the same probability (because your accuracy is great). What happens next?

If you finish early, your manager will think you’re probably not very skilled because you had to overshoot your estimations by 100%. And if you finish late, your manager will think you’re probably not very skilled because work took 50% longer. Either the case, they’ll probably assign you to more scrum training.

You see, the thing is, even in an idealised situation, you’re not supposed to win at this game no matter what. The moment you produce a number — be that hours, points, or pokemons — you’re screwed. Because everyone’s expectations will be anchored to the number one way or another. And it’s a wrong number to begin with.

To a manager

Well, hello there. Since you’ve made it to management, chances are you’re smart and will be less prone to refuting factual information. So, I’ll be blunt with you here. A manager has one job, to make sure that resources are applied optimally. And if your “management style” is rooted in estimations, you won’t be doing a stellar job at it. Here is why.

Due to the mathematical model I’ve described above, chances that your team’s estimations will be accurate and precise are pretty slim. The only people who deliver their projects consistently on time and budget is the US army; and they do that by grossly overestimating everything that moves. For a business entity that’s an F in resources allocation, which is basically your job description.

You obviously can’t underestimate requirements, because that’s a straight up F in management. So, you’re most likely to try pushing the team to find some form of a reasonable middle ground in their estimations. Due to the math I’ve described above it will fail roughly 60% of the time. When your efforts will eventually piss off enough senior engineers on the team, you will start paying roughly $50-70k per person for replacements in cash money, all while delaying your project even further. And yes, that’s an F in management.

So, repeat after me “estimations is a form of budgeting”. While budgeting works great in civil engineering, it is completely counterproductive in software development. Because software engineering is essentially a break through development, which is creative R&D work, which is inherently unpredictable.

There are better tools to manage software development than budgeting. And unless it sinks in with you, the team will have little luck changing their ways against your will.

So, what now?

I imagine, you’re probably sitting there by now, thinking to yourself: “well, thanks, Kai. who do you think you are crushing my world like this?“. And, look, I’m sorry for dragging you through this, okay? If it will make you feel any better, it pains me to write those things too; although, admittedly, I kind of like it.

But, now you have options. You can either forget all of this and go back to doing what you used to do. Or, you can come back in a week and read my next story. Because there is a way out of this mess.

Yeah, I know, a shameless plug. But hey, I have mouths to feed, and I need more eyeballs on my content. So, if you enjoyed the read, or find it useful, please share in your circles. Thanks muchly, and I’ll see you next time!