Managing quality beyond technical debt

The quality of software engineering is a bit of a beaten up topic. But, unfortunately, these conversations spend much of the time talking about technical debt and why it’s, well, bad. While that’s not wrong, the subject of quality is bit more complex than that, and today I wanted to share what I have learned so far.

Before we start, a quick disclaimer to avoid confusion. When I say the term “quality” here, I mean quality of a product as a whole, not just technical debt specifically.

The intuition

Generally speaking, most conversations about managing quality revolve around the following intuition. The better the quality the more expensive the product is. And the more expensive the product the less willing the customers are to pay for it, and hence we get less customers and profits.

If we add those two ideas together then it follows that some sort of an optimum state of ballance needs to be found between investing in quality and making profits. Which, generally speaking, makes sense.

Here is another idea that universally accepted as something that makes sense:

Fish rots from the head down

It sounds right and might even correlate with our experience, but it’s factually incorrect. Have you ever seen chefs picking up fish at a fish market? They always sniff fish tails, because that’s where it actually starts rotting.

The cost of quality

Quality practitioners use two terms to describe the quality management framework:

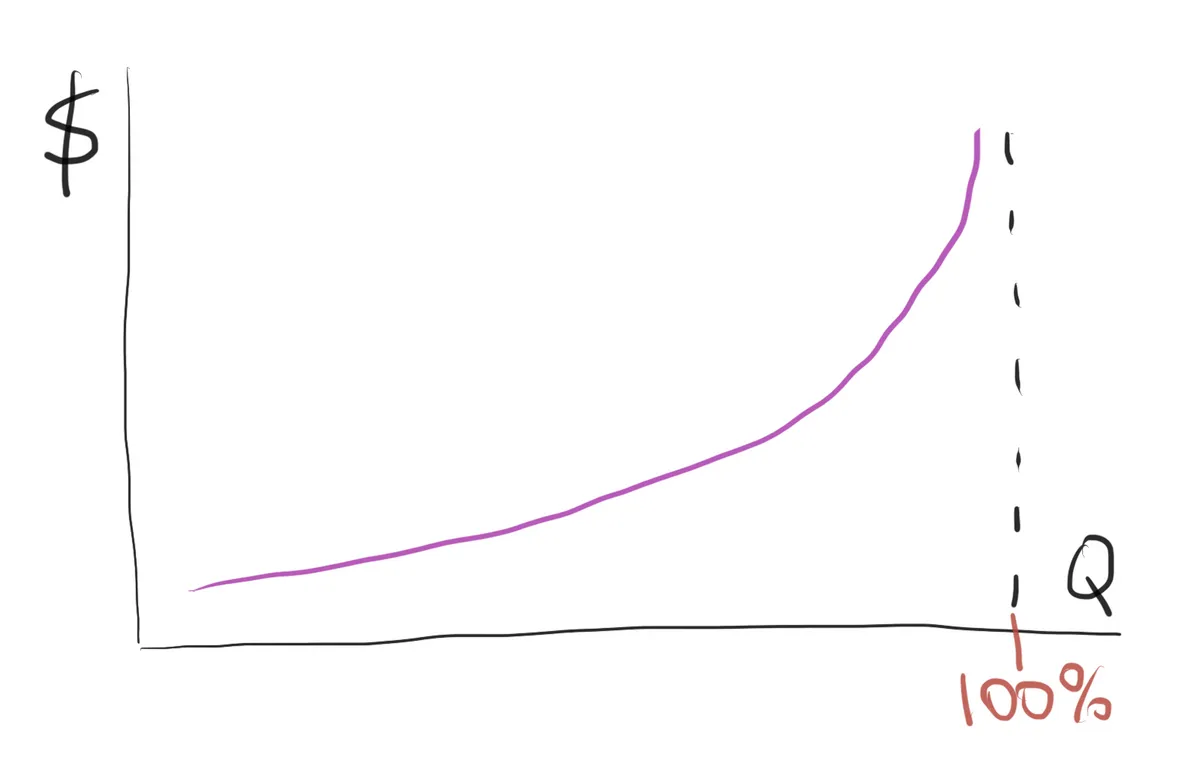

The cost of great quality - defines the amount of investments necessary to bring quality higher. Just as intuition tells us, the higher the quality the higher the cost. But, it’s not a linear relationship, it’s an exponential one. As in the initial investments buy more quality, but eventually quality stops growing with additional spending when it starts reaching perfection.

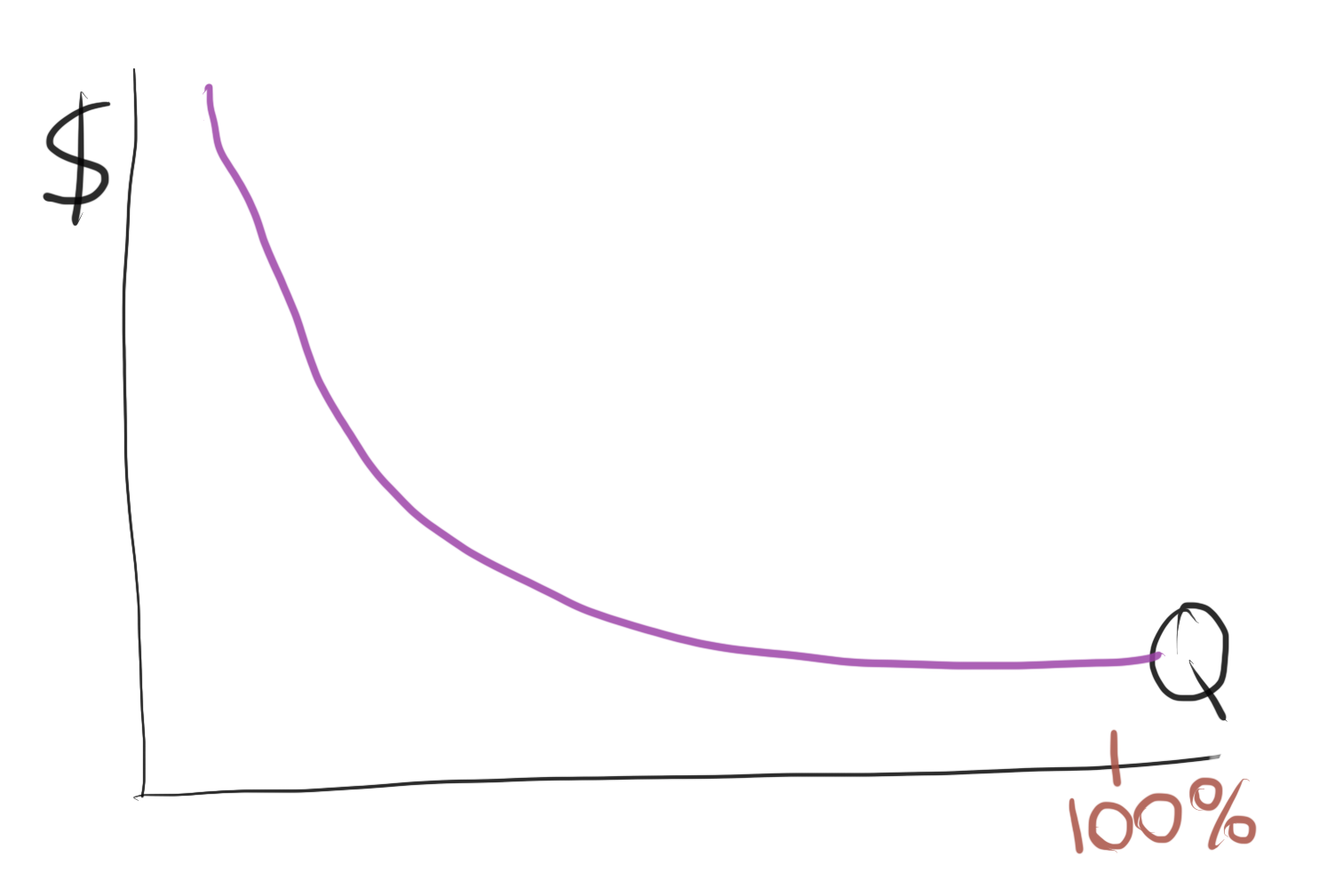

The cost of poor quality - defines the amount of investments necessary to maintain poor quality products. This includes costs such as operational costs associated with fixes, product recalls, customer management, missed opportunity cost, etc. Again a non-linear relationship, the initial small lapses in quality cost less than more major quality issues. Which in extreme situations can cost the company a business.

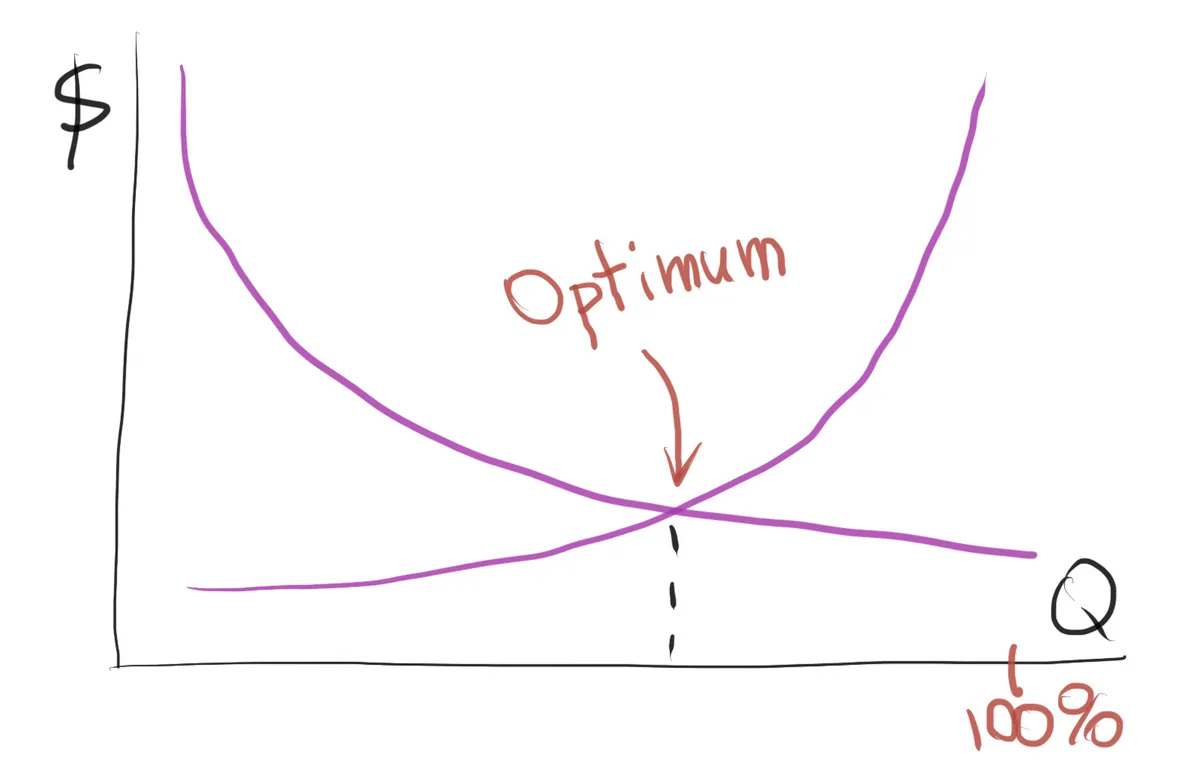

And so, if we put those two graphs together, we would expect to see an intersection of the lines, and that is what our intuition tells us is the sweet spot between cost and quality that will result in maximum profits.

And just as with the fish rotting from the head down, this seems intuitively like a sensible idea, except it is not factually correct.

The problem

The main fallacy here is that there is no scale to the picture. We’re sort of expecting that the cost of good quality and the cost of poor quality will revolve around the same numbers and intersect somewhere in the middle; like the supply and demand graphs.

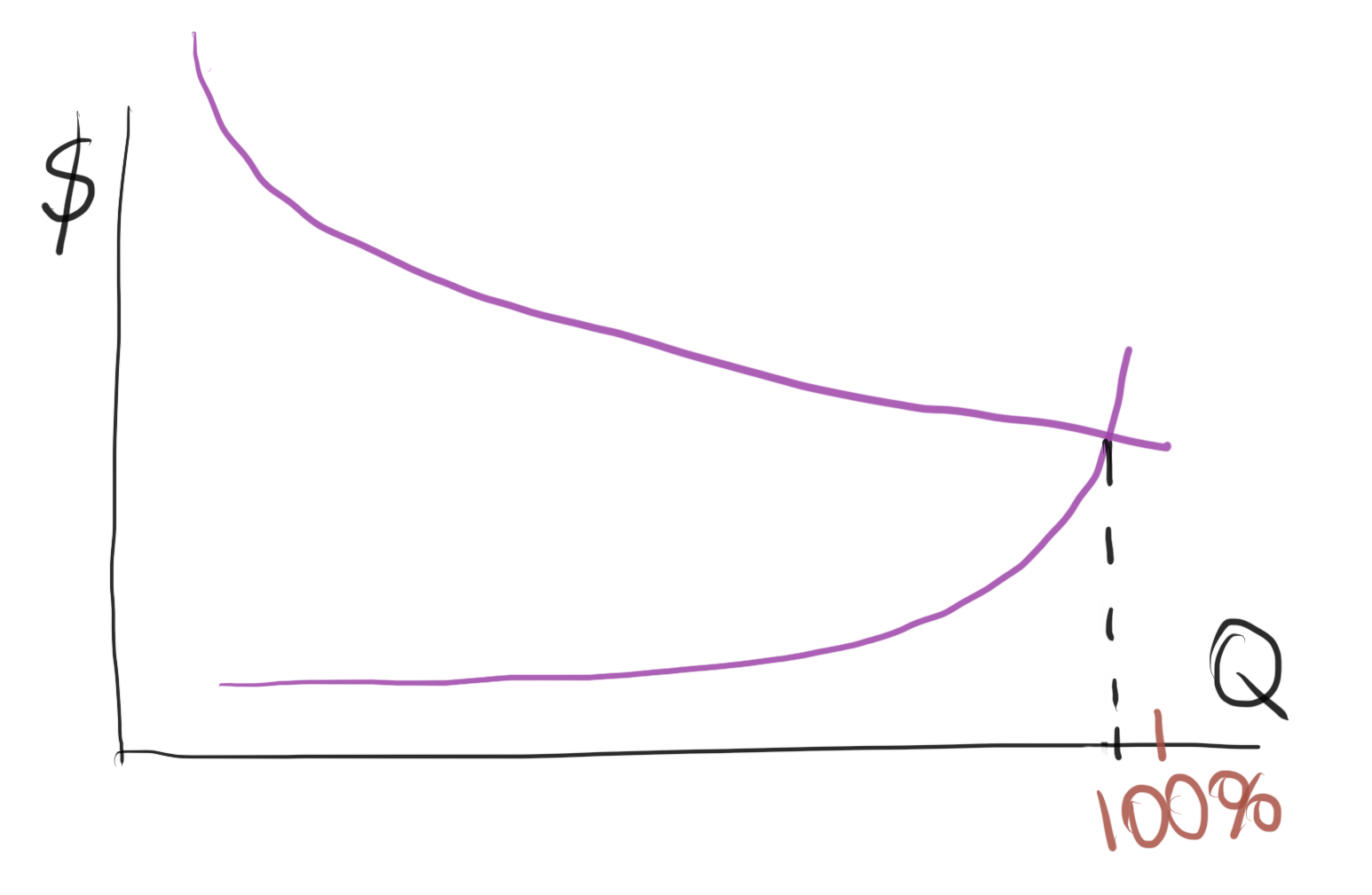

That is just not the cast in most situations. Most likely when put on the same scale the combined graph would look like so:

Generally speaking the gap between the cost of good quality and the cost of poor quality will depend on two things: production volume and margins. The higher the production volume the higher the poor quality overheads, because one has more customers to serve. And conversely, the lower the production margins, the lower the cost of good quality, because the cost of quality per an additional item is lower.

Now, if we think of an environment such as software engineering where the production volume can count in hundreds of millions of users, and production of an additional copy, aka margin cost, is virtually zero, it’s easy to understand that the gap between the cost of good quality and the cost of the poor quality will be exceptionally large.

Which means that in a well functioning software engineering company there is no really compromise to make or balance to find. The company should invest in as much quality as it can pull off, because the cost of poor quality grossly outweighs the cost of good quality.

Another dimension

There is yet another dimension to this problem as well. Because quality in products in not an uniformly distributed entity and actually has a deeper structure. Virtually any set of features that a product has could be divided into three categories:

- Baseline expectations - people don’t even think about those as features. For example, a car should have four fully inflated wheels and an engine.

- Required features - those are the features that people usually use to describe a product. For example, a car should be quiet on the inside, and it should have a good infotainment system, and it should be comfortable for a family of four.

- Delighters - those are the features that customers didn’t ask or even thought about, but they enhance the value of the product in the user’s eyes. Things like ergonomics or visual presentation would fall into this category.

This is related to quality because there are different quality expectations for each category of features. The baseline expectations should work every single time without a fail. For example a car must start, or a website must open up.

The required features should work most of the time as well, spared some exceptional circumstances: like for example some parts of your application could be unavailable due to a new deployment or a production bug. And delighters are expected to mostly work, but if they don’t it won’t affect the users much: say if the visual blings in an app stopped working for a day or two.

In practice

So, lets quickly recap what we have gathered so far. There are two main ideas:

- In a software product company the cost of poor quality grossly outweighs the cost of good quality.

- The internal structure of product quality dictates that the baseline features must have great quality as a default expectation, and required features should follow close behind. Meaning that 95+% of any application’s features are expected to have great quality.

Both of those ideas point in the same direction, that investing in quality as much as possible is the most sensible approach. Zero technical debt is the way to go.

Now, I don’t know about you, but I think this idea that you must invest in quality as much as possible won’t sit great with most people. Who would want to spend all their profits on quality, right? And once again, it’s just like with the fish rotting from the head, the contradiction seems sensible, except it is not factually correct.

When we step down to the real world practicalities, we will realise that spare extreme cases, the quality is not capped by the amount of money a company can pour into it, the quality is capped by the state the art of the mainstream technology that’s the company uses to create their products.

For example, the quality of cars or smartphones manufacturing is limited by the quality of the parts manufacturing process. Similarly the quality of a web application service is limited by the cloud infrastructure vendor’s SLA, and the security is limited by the security vendor’s guarantees.

Funding the quality

Spare some behemoth companies like Apple, Google, or Samsung that can invest in pushing technology beyond its limits and invest in getting even better quality of products, most companies rely on technology vendors and hence are limited by the best practices associated with these technologies rather than money that they can spend on quality.

Still, even best practice level product development costs money. And so, often times the conversation goes back to the idea that quality makes products more expensive, which in turn negatively impacts sales. So, I wanted to add a few points to that end as well.

The most likely situation where this might be the case is really when a company is trying to operate in an oversaturated market and doesn’t segment it’s offerings well. Meaning the company competes on margins rather than product offerings. In a narrow band of highly optimised market production costs will be everything, and unless the company invests in cheaper manufacturing processes they won’t be able to afford quality.

That is not entirely the case in the SaaS products markets. The reason is that the margin costs are near zero, which means that creating a 1-to-1 carbon copy of another product will mostly produce nothing but an IP infringement law suit.

Most half-decent product strategies in the SaaS market are inherently anticompetitive. Most successful software products operate in specific niches and hence the cost of great quality must be priced in. Because if the quality is not there, the company will instantly loose the bulk of it’s customers to a competitor that can make the same thing 10% better. Hence the products that ultimately succeed have the quality baked in as a default.

Wrapping up

There is actual science behind this madness. And if you’re interested in the actual statistical analysis and quantifiable methodology, I would strongly recommend diving into lean six-sigma. It’s not entirely software engineering, but the thinking and methods still apply.

If you’re not up for that, then here is a short wrap. As far as software development goes, you best bet is to use existing best practice as a default expectation. Better yet, if you have some resources to spare, investing in discovering better than the best practice will greatly improve the bottom line outcomes.

And conversely, operating on a level below best practice is basically throwing the money into the wind. The main reason why situations like that exist is because the company leadership never bothered to count the cost of poor quality, and the expenses that go into maintaining poor quality applications largely go unnoticed.