The beach

When we look at software engineering companies throughout the years, we can see patterns of interconnection between engineering and other functions. Bulk of the companies still treat engineering as a cost centre; an internal agency of sort. But, the industry is getting smarter, in many companies engineering gets integrated into cross-functional profit centers through autonomy and enablement practices.

But, I believe that the role of technology in a software development organisation goes further than mere cost vs. profit centre conversation. In the most disruptive organisations technology itself is elevated to the state of fundamental truth. That is how you build google maps, iphone, oculus rift, and ChatGPT.

I have this little metaphor that I like to tell to demonstrate the point.

The beach

Imagine a person walking a dog down a beach. The white noise of surf, a gentle breeze. The dog is snooping back and fourth across the curved lip of the sand. The person is lost a bit in their thoughts as they are trotting along.

The dog is making semi-random moves across the beach, and the person is slowly following it. If you look at their foot prints along the beach, it looks like a set of real-life data sampling smoothed with an exponentially moving average.

You can think of this image as a miniature representation of a software engineering company.

The hound is the marketing and sales department. They interact with the market non stop. There are tonnes of interesting and exciting things happening in the market all the time. New customers, new competitors, new opportunities. And they love chasing them all!

The person represents the product team. A person is dragged along by the dog. But the person doesn’t repeat the dog’s footsteps exactly. A person analyses what the dog finds and tries to makes sense out it. They enjoy each other company, but, it is the person who holds the leash and decides where they’re going.

The beach represents the engineering, or rather the technology itself. In the end of the day, this little story—a person walks out a dog at the beach—the path they take is defined by the curved shape of the beach. That is the context of this story; it defines what’s possible.

What is possible

In the age when SaaS products are literally designed for fast migration off competition, customer loyalty is a feeble thing. Building products with off the shelf parts and then pray that you won’t have copycats with better margins is just not a very smart idea. The product offering differentiation must go through and through, including the technology. And the edge needs to be carefully maintained over time.

Even in the b2b context where a vendor migration is a long and painful process, those multi-year contracts are normally signed with the expectation that a vendor will maintain their superiority long term.

And in that context, the most sustainable strategical foundation of any software engineering company is to innovate relentlessly ahead of the competition. It’s a classical red queen problem, a successful company has to innovate non-stop and as fast as it can just to stay where they are.

Systems thinking postulates that any complex system’s behaviour is a result of it’s internal structure. The beach, the person, and the dog is the internal structure of most modern agile software development organisations; they all play in roughly the same field in that aspect. And, it is this internal structure that produces the behaviour we see, and, ultimately, separates successful companies from those that perish way too soon.

The agile way

When I think of the beach I see a technology possibilities space with an overlay of customer adoption data. There is a lot that can be built with technology, but not all of it will spark the customer’s interest.

In this sense, the contemporary iterative agile practices is a way to search this space for something useful. Like the dog on the beach that is following the smells, we follow the customer feedback. We’re trying to find where the customer’s interest is clustered, and then build technology around that space.

And so, we follow the scent, and then we build around the hotspots. In a way we give the customer what they want. But, however sensible this sounds, there is a fallacy in this thinking. Because what the customer wants and what customer needs, is usually not the same thing.

The way of agile can be summarised like so:

Always listen the customer’s problems. Never listen to the customer’s solutions

In this technical possibilities space, the most disruptive solutions are not located in the same spot where the customer wants are. When apple introduced iPhone people didn’t want an iphone, they wanted a better phone. When google introduced Gmail people didn’t want gmail, they wanted a better web-mail. When microsoft introduced LLMs, people didn’t want LLMs, they wanted a better AIs.

The algorithm

The closest concept to agile practices in computer science that I can think of is genetic algorithms. GAs is a search heuristic to explore multi-dimensional possibilities spaces that works on iterative mechanics. In general terms it works like so:

idea = initial_idea()

while solution_is_getting_better():

options = generate_options_from(idea)

idea = find_best_among_new(options)Essentially, it is an iterative search process. At every step we explore possible steps forward, pick the best option and keep on moving. The actual real life implementation of this process can be rather complex, but the idea is quite simple and elegant; just like the process of evolution in the nature.

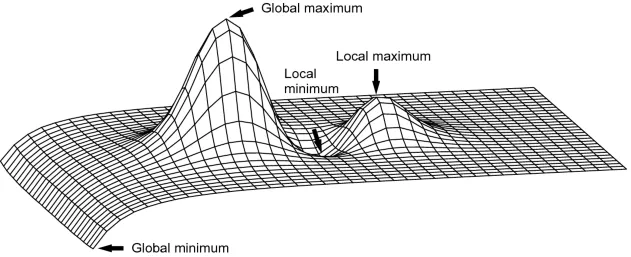

This type of search algorithms has one massive flaw, though. They all have a tendency to get stuck in local maximums. Just like a team blindly following customer’s feedback, those algorithms find something that works, but never can punch through the negative space surrounding it to ever find the true maximum.

There is a long list of ways computer science is trying to deal with this issue. But, they all basically boil down to the same point: they introduce some ways to explore other options than a straight up gradient descent. Usually it manifests in random leaps outside of the normal exploration path.

Final notes

We can endlessly jump between abstractions and their real life manifestations like this. And, we will see exactly the same pattern emerge. In complex systems facing limited computational resources, methodical search is rarely the optimal approach.

The idea is rather counter intuitive, that in order to be effective in a random complex environment, we need to introduce more randomness in our process and explore options outside of the normal search path. But, I think Steve Jobs gave it a good point of view.

The customer doesn’t know what they want

-- Steve Jobs

The thing we all keep forgetting at times is that in this industry, we’re not as much bringing technology to the customers, as we bring the customers to technology. The idea that we iterate to find out what the customer wants is an illusion. In practice, we do the opposite of that, we iterate on an idea in hopes that it will attract the customer.

And those initial ideas come from the technological possibilities space; from finding out what’s possible. The beach, the technology itself is the fundamental truth in this story.

So, don’t just blindly follow the dog, explore the beach too.